COVID-19 impact on bladder cancer-orientations for diagnosing, decision making, and treatment

Thiago C Travassos, Joao Marcos Ibrahim De Oliveira, [...], and Leonardo O Reis

Introduction

The world is going through an unprecedented time in history with the arising of COVID-19. In the past, epidemics were something not as unusual as they are today, but humankind never faced a so global and widespread disease like the one caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Like many Oncology physicians, Urologists are facing and combating on two fronts: against the pandemic itself and cancer. Among all genitourinary cancers, bladder cancers are, probably, the most challenging one regarding timely decision making. Patients are usually in their late 60 s and early 70 s, more vulnerable against COVID-19, have multiple comorbidities and some will need chemotherapy.

Regarding fatality rates, bladder cancer overcomes COVID-19 by far, however, it is not the only aspect Urologist must aim at. A lot of panics have been spread in the last months, many patients are worried to be submitted to surgeries and even seeking help for health issues; and, as a consequence of it, a great percentage of them will suffer, not from the virus itself, but the consequences of it in the healthcare systems and on the psychological and dynamics of the individual and the society.

The questions are: who should be investigated and submitted to the environment of hospitals or clinics, how to investigate in the most efficient way, which patients can wait, which will need to be treated, what is the best way to treat each stage of the disease and how to proceed with these patients’ follow-up.

History has proven that pandemics have an end; but in the meantime, Urologists will have to decide which patients to expose to the health system, which ones will need more urgent intervention, and above all, to think how decisions will reflect on patients and the healthcare system in the short and long-term, with implications for years to come.

Patients with low-grade non-invasive bladder cancer have a reduced potential for disease progression when compared to patients with the muscle-invasive disease. Postponing a cystectomy surgical procedure or completing neoadjuvant chemotherapy beyond 12 weeks puts the disease’s progression and stage at risk [1].

Although follow-up cystoscopies can be performed on an outpatient basis, the risk of COVID-19 infection should not be disregarded, and the postponement of this procedure should be used to prioritize patients with a higher risk of disease progression. Regarding the previous standard follow-up, examinations of patients with non-invasive bladder cancer may be postponed, while the muscle-invasive must have a more rigorous follow-up, considering the risk-benefit of early diagnosis of relapse and thus the treatment [2].

Based on the current literature on optimal bladder cancer patients approach we comprehensively synthetize the major societies guidelines on the issue so far, adding a critical view to the topic. This article aims to guide Urologists on decision making against bladder cancer in the COVID-19 era.

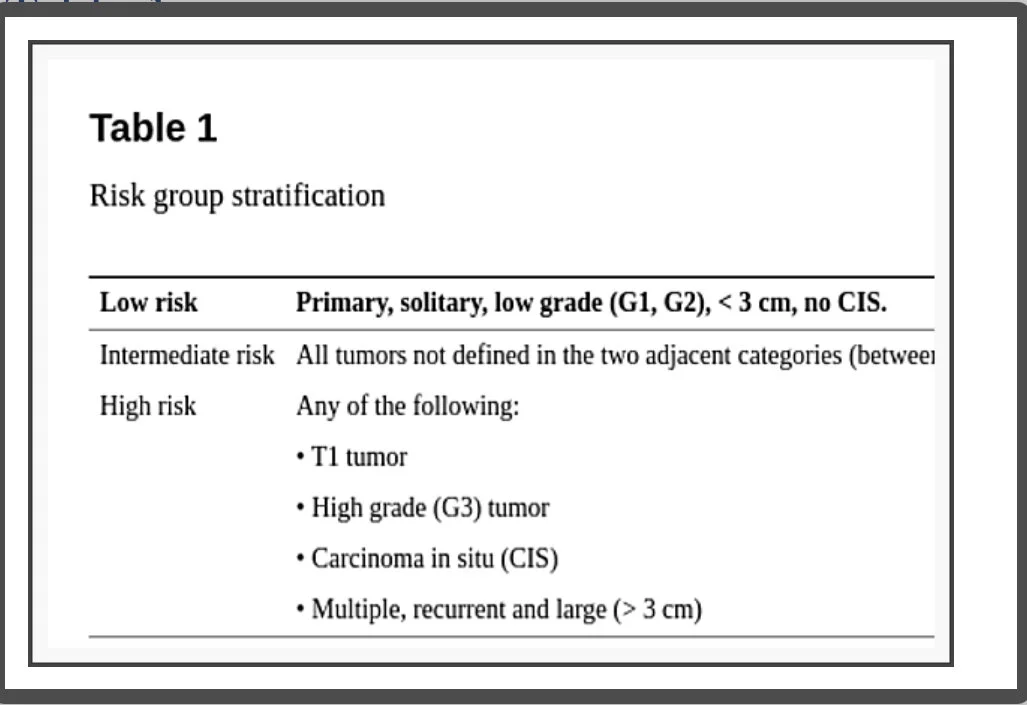

The patient approach based on data analysis and risk stratification (Table 1)

Risk group stratification

One of the worst days of patients’ lives is at cancer diagnosis and it can significantly worsen if the appropriate care access is limited. That’s the dilemma Urologists have in their hands.

The global burden of bladder cancer is significantly high, representing 3.0% of all new cancer diagnoses, 2.1% of all cancer deaths in 2018 [3], and the 10th most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide. In Europe, the incidence and mortality rates are higher in the Southern; in 2018 the age-standardized incidence and mortality rate were 15.2 per 100,000 inhabitants and the number of deaths was 64,966 [4].

Regarding the United States (US), the annual death rate from 2013 to 2017 (adjusted to the 2000 US standard population) was 4.4 per 100,000. For 2020, the American Cancer Society estimates 81,400 cases of bladder cancer, which represents 4.5% of all new cancer cases, leading to 17,980 deaths [5].

COVID-19 data changes every day. The April-26th 2020 World Health Organization (WHO) Situation Report showed a total of 2,804,796 confirmed cases, 193,722 deaths. Spain registered 219,764 cases and 22,524 deaths and the United States 899,281 cases, with 46,204 deaths [6].

In absolute death numbers, COVID-19 beats bladder cancer by far, but the analysis of the numbers can be very confusing and uncertain because of differences in adopted models used for data measuring. Even when the correct epidemiological terms are used, the number of tests and the eligibility criteria for doing it can, alone, make fatality rates vary from 0.35% in Israel to 11% in Italy at the end of March 2020. WHO Situation Report, shows a 6.9% overall case fatality rate [7].

But how to compare all of these numbers? Once diagnosed with bladder cancer the overall case fatality rate all over the world (2012) and in the United Kingdom (2015-2017) were respectively 38% and 52%, and it is estimated to be 22% in the US for 2020. The situation can be analyzed from a different perspective. COVID-19 has, indeed, killed many people; but mostly because of its great potential of spreading (infections and cases) since its fatality rate remains low. On the other hand, when someone is diagnosed with bladder cancer the chance of dying of it can be as high as 52%, so the consequences of delaying definitive treatment might impact clinical outcomes and be felt far beyond the COVID-19 outbreak, for years to come [8].

Even so, some considerations are important for shared decision making. A pandemic outbreak puts the healthcare system under extreme pressure. Many hospitals are interrupting elective surgeries to preserve health teams, ventilators, standard rooms, and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) capacity.

The American College of Surgeons advises that decisions about proceeding with elective surgeries should not be made in isolation, but use frequently shared information systems and local resources constrain, especially protective gear for providers and patients. “This will allow providers to understand the potential impact each decision may have on limiting the hospital’s capacity to respond to the pandemic. For elective cases with a high likelihood of postoperative ICU or respirator utilization, it will be more imperative that the risk of delay to the individual patient is balanced against the imminent availability of these resources for patients with COVID-19” [9].

Patients have to be aware that surgery, even during the incubation period of COVID-19, can be a risk factor for postoperative complications, ICU need, and mortality. It’s also important to look deeply into a specific age fatality rate. In China, approximately 80% of deaths occurred in people over the 60 s. In the United States 31% of cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths happened among people at the age of 65 or more. Using March/2020 as a parameter, while the overall case fatality rate was 3.5%, case-fatality rates varied from 2.7 to 4.9% at 65-74 to 4.3 to 10.5% at ages 75-84, showing that age plays an important role in outcomes, especially in the age range when bladder cancer is more prevalent. Patients have to know that the real scenario, an ongoing pandemic, can be vastly underestimated and that data and protocols can change day by day [7,8].

Patient selection to undergo cystoscopy

Two different situations must be distinguished: (1) Patients not yet diagnosed with bladder cancer and (2) Follow-up patients [10].

Macroscopic hematuria is per se a very challenging symptom for Urologists as it is frightening for patients. Both truths added to COVID-19 make its management even more challenging. Although no internationally accepted uniform algorithm exists, visible hematuria always requires investigation as its presence represents a risk of about 20.4% malignancy while in microscopic hematuria this risk is around 2.7%. Cystoscopy remains the diagnostic test of choice for bladder cancer and in cases of unequivocal lesions on US or urography computed tomography the indication is to proceed immediately to transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) [11,12].

The fact is that the ideal, painless, outpatient, flexible cystoscopies are not the reality in most developing countries where the procedures (rigid cystoscopy) occur in the operation room during hospitalization, exposing the patient, even if for a brief period, to the hospital environment.

Despite that, in the presence of macroscopic hematuria the Cleveland Clinic and the American Urological Association (AUA), recommend performing full evaluation without delay, as scheduled. In the presence of microscopic hematuria with risk factors (smoking history, occupational/chemical exposure, irritate voiding symptoms), diagnostic cystoscopy can be delayed up to 3 months unless the patient is symptomatic. If there are no risk factors, evaluation can be delayed as long as necessary [13].

Regarding follow-up, the EAU divides situations into four levels of priority according to clinical harm (progression, metastasis, loss of renal function) risk. (1) Low: very unlikely if postponed 6 months; (2) Intermediate: possible if postponed 3-4 months, but unlikely; (3) High: clinical harm and cancer-related death very likely if postponed for more than 6 weeks; (4) Emergency: a life-threatening situation or opioid-dependent pain, treated at emergency departments despite current pandemic [14].

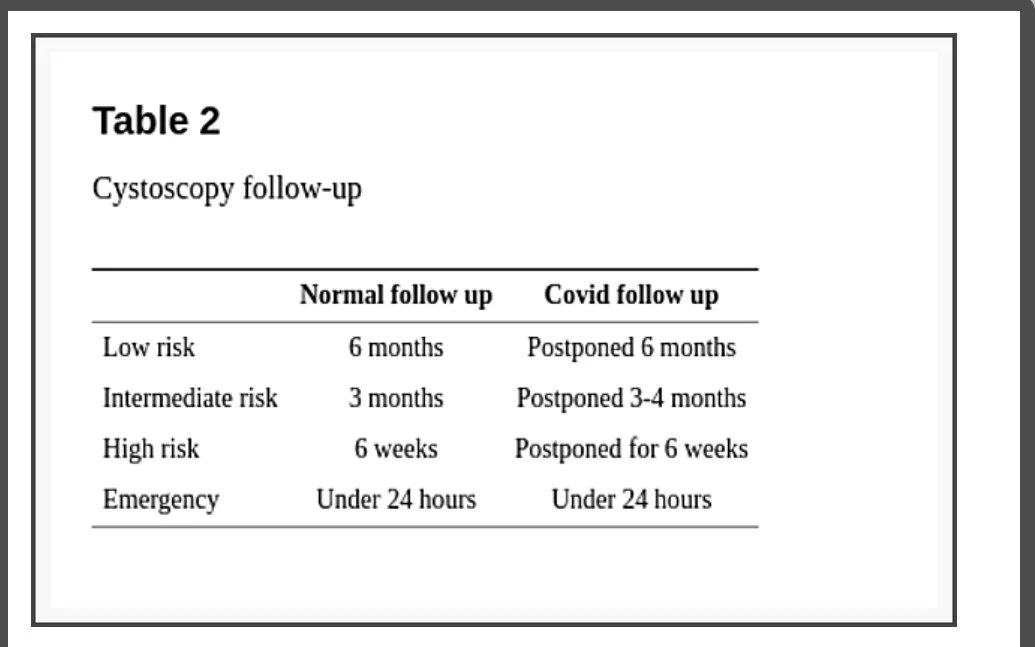

The recommended for low priority bladder cancer, patients with low or intermediate-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) without hematuria, is to defer cystoscopy by 6 months. Intermediate priority patients, with a history of high-risk NMIBC without hematuria, might be followed up before the end of 3 months. High priority patients, with NMIBC and intermittent hematuria, must undergo follow-up cystoscopy in a period inferior to 6 weeks. In case of emergencies (visible hematuria with clots, urinary retention) cystoscopy or TURB must be considered within less than 24 hours (Table 2). EAU guideline is the only one to specify the level of confidence of its recommendations (all the above-cited, level 3) [14].

Cystoscopy follow-up

AUA guideline recommends considering surveillance cystoscopy without delay for assessment of response to treatment or surveillance of high-risk NMIBC within 6 months of initial diagnosis. For high-risk NMIBC beyond 6 months of initial diagnosis, the recommendation is to consider delaying evaluation for up to 3 months. Assessment of response to treatment or surveillance of low/intermediate-risk NMIBC regardless of when the diagnosis was made may be delayed for 3 to 6 months [13].

Considerations regarding computed tomography and hematuria

All over the world, SARS-CoV-2 is putting healthcare systems under a lot of pressure, and computed tomography (CT) is being used for diagnosis, management, and follow-up of COVID-19. Although CTs, using specific urological protocols, is the gold-standard method for the investigation of most urological pathologies, this new scenario is forcing Urologists to review and adapt.

The DETECT I (Detecting Bladder Cancer Using the UroMark Test), a prospective, observational, multicentric study showed that patients with microscopic hematuria had 2.7%, 0.4%, and 0% incidence of bladder cancer, renal and upper tract urothelial cancer, respectively, and that the approach with cystoscopy and renal and bladder ultrasound (RBUS), instead of CT could be used, in cases of microscopic hematuria. On the other hand, RBUS accuracy alone to detect bladder cancer was poor with 63.6% sensitivity, reinforcing that for bladder cancer diagnosis, cystoscopy remains the gold standard and CT urography continues to be the upper tract investigation method of choice [15].

In concern to follow-up, EAU guideline is the only one that provides some guidance and recommends to defer by 6 months upper tract imaging in patients with a history of high-risk NMIBC (low priority) [14].

Therapeutical and surgical indications for patients with bladder cancer in the COVID era

AUA is following the guidance of the American College of Surgeons which devised surgeons to look at the Elective Surgery Acuity Scale (ESAS) from the St Louis University for decision making during the COVID-19 outbreak. This scale is graduated from tier 1 to 3, with subdivisions (a) and (b). Most cancers are classified as 3a (high acuity surgery/health patient) which must not be postponed. There is no specific mention regarding bladder cancer patients [16]. The Cleveland Clinic Department of Urology is more specific regarding procedures as it stratifies patients from 0 (emergency) to 4 (nonessential) and specifies surgeries; although its tables and text are very poor at explaining acronyms. In this guideline cystectomies (high-risk CA) and TURB (high-risk) are stratified as 1 (0-4) while TURB low risk, as 4 [13].

EAU guideline uses the same method for cystoscopy, strafing patients in priority categories (low, intermediate, high, and emergency) and is more specific and complete [14]. We will summarize all recommendations, dividing the disease in its classic risk stratification, using, mainly, EAU guideline, because of its consistency. It is not the scope of this article to discourse about the TNM staging system and it will be used as in EAU guideline. Also, important to say that most of the statements were directly extracted from the guideline but rearranged, in a more didactic way.

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

According to EAU guideline [14] TURB can be delayed by 6 months in patients with small papillary recurrence/s (less than 1 cm) and a history of Ta/1 low-grade tumors. If feasible maybe just followed or fulgurated during office cystoscopy. The second TURB in patients with visibly complete initial TURB of T1 lesion with muscle in the specimen can also be deferred by 6 months. In these cases, TURB also can be postponed after Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) intravesical instillations.

Patients with any primary tumor or recurrent papillary tumor greater than 1 cm and without hematuria or history of high-risk NMIBC must be treated before the end of 3 months. In cases with bladder lesions and intermittent macroscopic hematuria or a history of high-risk NMIBC, TURB must be done within less than 6 weeks. All patients confirmed or suspected of bladder cancer presenting macroscopic hematuria with clot retention or/and requiring bladder catheterization ought to be treated in a time inferior to 24 hours. Any patient with the highest-risk NMIBC must be considered for immediate radical cystectomy.

Muscle invasive bladder cancer

According to EAU guideline [14] In cases when Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC) is diagnosed, staging imaging by CT thorax-abdomen-pelvis should not be delayed. On the other hand, in cases when images are suspicious for invasive tumors, TURB must be performed. In both cases, CT or TURB must be done in 6 weeks.

The proven benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in T2 tumors, is limited and has to be weighed against the risks, especially in patients with a short life expectancy and those with (pulmonary and cardiac) comorbidity. The same is valid for focal T3 N0M0 tumors. That cisplatin eligible, high burden T3/T4 N0M0, NAC risk should be individualized while they are on the waiting list, but treatment should be offered before 6 weeks. All inclusion in chemotherapy trials must be delayed, except for cisplatin eligible patients.

Regarding radical cystectomy (RC), it can be offered for patients with T2-T4a, N0M0 tumors and must be performed before the end of 3 months. Once RC is scheduled the urinary diversion or organ-preserving techniques should be done as would be planed outside this crisis period. Multimodality bladder sparing therapy can be considered for selected T2N0M0 patients [17]. In cases where palliative cystectomy is considered as intractable hematuria with anemia, alternatives such as radiotherapy (RT), with or without chemotherapy, must be discussed. In the presence of anemia, it is important to start treatment in less than 24 hours, other palliative cases may wait not more than 6 weeks.

Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy can be offered to those patients with pT3/4 and/or pN+ disease if no NAC has been given and must be started in less than 6 weeks.

Metastatic bladder cancer

Oncologists play a central role to advise the feasibility of non-surgical treatments like radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the management of malignancy mainly in these uncertain times the world is facing [17]. In the words of Dr. Thomas Powles, Professor of Genitourinary Oncology and Director of the Barts Cancer Centre in London, “(…) if you’re going to give chemotherapy today (…) Don’t think about what it looks like today. Think what might it look like in two weeks before you push the patient into that swimming pool, not knowing how long they’re going to be under the water for” [18].

The key point is to assess risk and benefit individually in each patient. In asymptomatic patients with low disease burden, the first-line therapy can, in selected cases, be postponed to 8-12 weeks under clinical surveillance. EAU guideline recommends the use of cisplatin-containing combination chemotherapy with GC (gemcitabine plus cisplatin), MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin plus cisplatin), preferably with G-CSF (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor), HD-MVAC (high dose-MVAC) with G-CSF or PCG (paclitaxel, cisplatin, gemcitabine). In this period (inferior to 3 months) offer checkpoint inhibitors pembrolizumab or atezolizumab depending on PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1) status [14].

In symptomatic metastatic patients, the benefit of treatment is likely higher than the risk and these patients should initiate treatment within less than 6 weeks. Supportive measures such as the use of GCSF should be considered. The recommendations are the same for the asymptomatic patients being treated. As second-line therapy, checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab can the offered to patients progressing during, or after, platinum-based combination chemotherapy for metastatic disease. Alternatively, offering treatment within a clinical trial setting can be an option [14].

Supportive care

The EAU guideline recommends that acute renal failure, for locally advanced bladder cancer, must be treated with nephrostomy at ambulatory settings [14]; not a reality for most developing countries in the world, where nephrostomies are done in the operating rooms with improvised materials. Embolization or hemostatic RT ought to be considered for bleeding with hemodynamic repercussion.

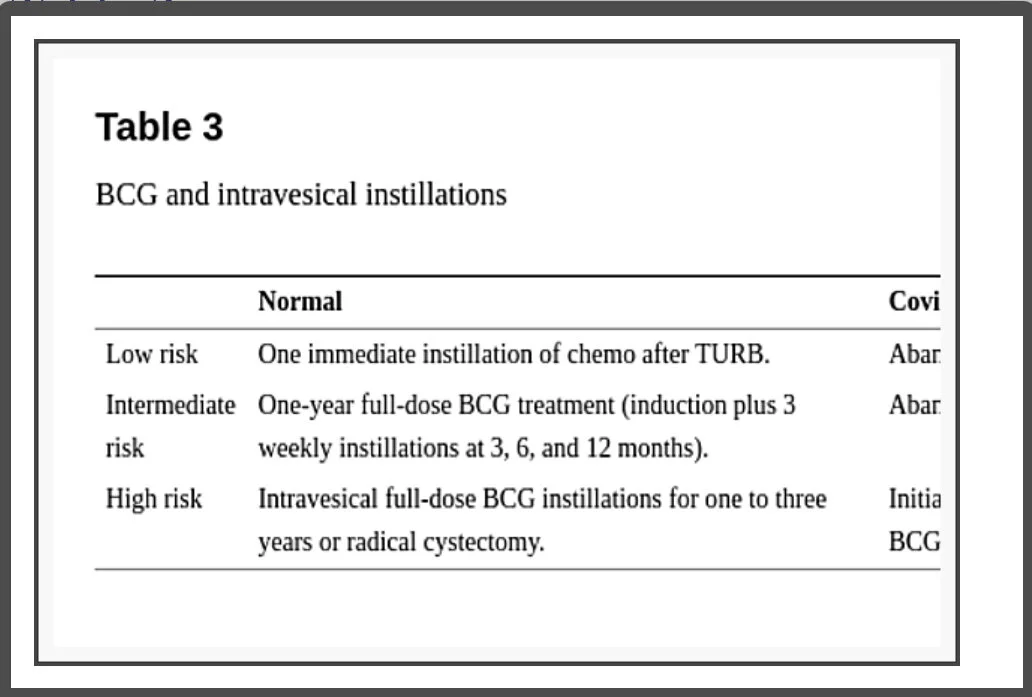

Considerations regarding BCG and intravesical instillations (Table 3)

BCG and intravesical instillations

There is no evidence that patients receiving intravesical BCG have a higher risk of COVID-19 and the recommendation for not initiating, stopping, or postponing are mainly because the risk of contracting the virus when going to a health care facility might overcome the risk of delaying doses for some time.

EAU guidelines orientate to abandon early postoperative instillation of chemotherapy in presumably low or intermediate-risk tumors as in confirmed intermediate-risk NMIBC. In high-risk NMIBC the recommendation is to initiate treatment within less than 6 weeks with intravesical BCG immunotherapy with one-year maintenance [15]. AUA guideline recommends that, for intermediate and high-risk NMIBC, induction BCG should be prioritized, once induction provides a significant benefit by reducing disease recurrence and progression; though they may also require a delay in therapy depending on local needs and resources. On the other hand, maintenance intravesical BCG should be stopped and reevaluated in 3 months for high-risk and delayed indefinitely in intermediate-risk because the most significant impact of the intravesical treatment is obtained during the induction course [13].

Does BCG immunotherapy impact COVID-19? A study including 40 individuals that received the trivalent influenza vaccine, 14 days after randomly (20 × 20) being injected with BCG or placebo shows potential [19]; there is a therapeutic (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04369794) and some preventive trials underway studying the effect of BCG vaccination on increasing resistance to infection and preventing severe COVID-19 infection. Also, regarding intravesical BCG potential cross-protection against COVID-19, considering its T cell boosting mechanisms, we are starting the “Global Inquire of Intravesical BCG As Not Tumor but COVID-19 Solution” - “GIANTS” trial.

Considerations regarding surgical procedures

Viral RNA has been detected in feces from day 5 up to 4-5 weeks after symptoms in moderate cases. Wang et al., investigated the biodistribution of SARS-CoV-2 in different tissues, collecting 1,070 specimens from 205 patients with COVID-19. Of the feces samples, 29% tested positive compared to only 1% (3 of 307) blood samples, and none of the 72 urine samples, confirmed by another recent study where the virus was not detectable in the urine of tested patients [20,21]. These data have clear implications for surgeons when considering radical cystectomy and make TURB a more comfortable environment. Whenever possible, Urologist should test their patients for SARS-CoV-2 48 hours before surgery, not a very feasible reality in most developing countries.

Regarding laparoscopic surgery, many considerations can be done and full discussion of it is far beyond the objective of this article, even though some are worth discussing. Despite no conclusive evidence regarding the difference in risks of viral transmission, of open and laparoscopic surgery for the surgical team, the last one can be associated with a higher amount of smoke particles in the operation room. Recommended modifications are to keep intraperitoneal pressure as low as possible, to aspirate the inflated CO2 before removing the trocars, and to lower electrocautery power settings. Laparoscopic procedures, due to the lack of evidence for not performing it during the COVID-19 outbreak, must be considered as any minimally invasive procedure, that might be associated with shorter length of hospital stay, use of resources, and personal [22].

For robotic surgeries, the same cautions must be taken with some particularities, as avoiding using two-way pneumoperitoneum insufflators to prevent pathogens colonization of circulating aerosol in the pneumoperitoneum circuit or the insufflator. These integrated flow systems need to be configured in a continuous smoke evacuation and filtration mode. Aerosol dispersal is even more important when concerning robotic surgeries because of the common need of a not exchangeable operating room where the mobile cart, the image cart, and the console are at more risk of contamination due to particles in the air [23].

Conclusions

When comparing diseases and their epidemiological impacts, the mortality rates are a very common thermometer to help healthcare administrators and physicians on decision making, but when facing a novel disease as COVID-19, there has not been enough time to evaluate the damage regarding mortality. When looking at the fatality rates, bladder cancer overcomes COVID-19 by far and can be as high as 52%, so Urologists must not postpone investigation. Cystoscopy remains the gold standard for the investigation of bladder cancer and CT urography for obtaining images of the upper tract in cases of macroscopic hematuria. The use of ultrasound is reserved for imaging the upper tract in cases of microscopic hematuria. EAU guideline provides the most specific orientations in cases of bladder cancer and they are summarized above. Whenever TURB is necessary, extra care must be taken to assure muscle sample, avoiding another surgical intervention and hospitalization, but when necessary it should not be postponed due to the elevated progression rate of the disease. With this study, we can propose a new way to perform the screening and monitoring of bladder cancer, considering the aggressiveness and the capacity to progress depending on its stage. Follow-up cystoscopies can be postponed for 6 months for low risk, 3 months for intermediate, 6 weeks for high risk, and no longer than 24 hours in case of emergencies such as life-threatening hematuria, anemia, and urinary retention. This innovation in monitoring can bring greater safety to the patient, especially in those at higher risk, prioritizing and preventing the progression of the disease and guaranteeing their agile treatment when necessary, since the centers will have more time to schedule cystoscopies during pandemics. Regarding chemotherapy, more than ever the key point is to evaluate each case individually. BCG must be considered only as an inducing course, in selected intermediate and most high-risk cancers; all others should be stopped. Whenever possible patients should be tested before surgery.

Research involving human participants: The authors certify that the study was performed under the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.