Mapping overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer in China

Globally, the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased substantially in the past three decades,particularly among young adults and even in adolescents,whereas mortality due to thyroid cancer has remained relatively stable at low levels, or decreased, almost everywhere.The intense scrutiny of the thyroid gland and widespread use of ultra- sonography and other modern diagnostic techniques have allowed the discovery of a large reservoir of previously undetectable, small, and predominantly papillary thyroid tumours. Thus, the epidemic of thyroid cancer is likely to be predominantly driven by overdiagnosis—ie, the diagnosis of cancer that would not go on to cause symptoms or death in a patient’s lifetime. Overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer has been estimated to account for up to 60–90% of the diagnosed cases in several countries.

This phenomenon might be affecting China,1 where thyroid cancer is the fastest growing cancer, with an average 20% annual increase over 2003–11.However, substantial geographical variability exists, with an approximately 45 times difference between areas with lowest and highest incidence,5 the reasons for which remain unclear.

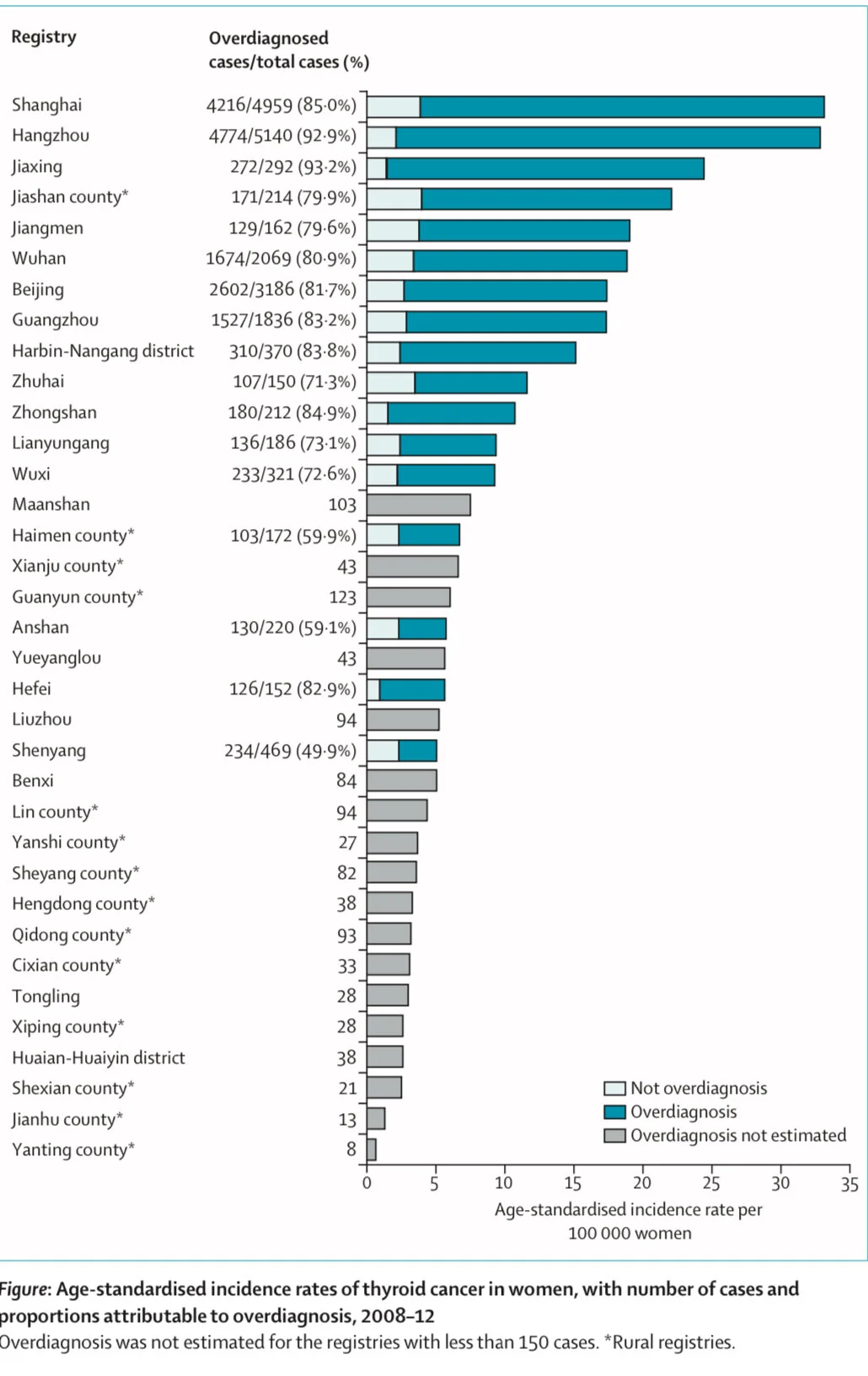

In this study, we explored the epidemiological features and the impact of overdiagnosis on thyroid cancer across regions of China, using population-based data from 35 cancer registries in mainland China included in the Cancer Incidence in Five Continents (CI5) database for the period 2008–12. In this period, 27 842 individuals aged 15–84 years were diagnosed with thyroid cancer (appendix pp 2–5). The average age- standardised incidence rate was 16.8 cases per 100000 women and 5·3 cases per 100 000 men. We found a large variability across registries in the age-standardised incidence of thyroid cancer, ranging from 0.7 to 33.9 cases per 100 000 women (figure) and from 0·4 to 11.6 cases per 100 000 men (appendix p 6). Higher incidence rates were observed in the 21 urban registries (an average age- standardised incidence 19.0 cases per 100000 women and 6·1 cases per 100000 men) than in their rural counterparts (4·9 cases per 100000 women and 1.4 cases per 100000 men). This geographical variation reflected predominantly the incidence of papillary carcinoma, which accounted for most of the diagnosed thyroid cancer cases in all registries (appendix p 7).

For ten registries with at least 10 years of registration data available (for 2003–12), we also assessed the temporal change of age-standardised incidence rates from 2003–07 to 2008–12, in absolute terms and as percentage of variation. We found increases of more than 10 cases per 100000 women and 5 cases per 100 000 men, with relative changes during this period exceeding 100% in Shanghai, Jiaxing, and Jiashan county (appendix p 12).

Contrary to incidence and similarly to what has been observed in other countries,thyroid cancer mortality remains low in China Previous studies have shown that the age-standardised mortality rate of thyroid cancer was 0·35 deaths per 100 000 women and 0.19 deaths per 100 000 men in 2010,far below the observed incidence, with an incidence-to-mortality ratio exceeding 40 in women and 20 in men. Even in high-incidence areas such as Zhejiang province, where the registries of Hangzhou, Jiaxing, and Jianshan county are located, age- standardised mortality of thyroid cancer remained stable at relatively low levels in the period 2000–12.7

A distinct epidemiological feature of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis that has been observed globally is that the increase in incidence is typically accompanied by a shift of the age at diagnosis, with a peak at around middle age (35–64 years), instead of at older ages (65–84 years), as was observed before the 1980s.Indeed, when plotting incidence against age at diagnosis in 2008–12 many regions of China followed this pattern, resembling an inverted U-shape, which was particularly pronounced in urban areas with high age-standardised incidence rates and large cities like Shanghai and Hangzhou (appendix p 8) but much less prominent in rural registries, except for Jiashan county (appendix p 9). Women in particular were found to be diagnosed early in life (age 30–49 years), probably due to their greater access to the health system than men due to gynaecological and obstetrical reasons, leading to increased chance of having their thyroid scrutinised by ultrasound. Unfortunately, data on the number of ultrasound machines in the study areas are not available.

We calculated overdiagnosis on the basis of the difference between the observed and the expected age-specific incidence, where the expected age curve was assumed to correspond to a scenario without overdiagnosis (ie, incidence increasing with a power law of age, as in historical patterns and in agreement with the multistage model of carcinogenesis; appendix pp 2–3). For all 21 registries in urban areas combined, we estimated that overdiagnosis accounted for 16 721 (83.1%) of 20 114 thyroid cancer cases in women and 4986 (77.3%) of 6452 cases in men in 2008–12. The highest proportions of overdiagnosis were estimated for Shanghai, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Beijing, and Guangzhou, accounting for over 70% of all thyroid cancer cases for both sexes (figure; appendix p 6). For all 14 rural registries combined, we estimated that 597 (60.4%) of 989 thyroid cancer cases among women and 170 (59.2%) of 287 cases among men were overdiagnosed.

We further assessed the possible role of availability and access to health care in China that, together with screening prevalence and socioeconomic development, has been found to be positively associated with incidence of thyroid cancer in previous national and international studies.We found that the age-standardised incidence of thyroid cancer was strongly associated at the regional level with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and with the number of hospital beds per 1000 people in both sexes (appendix pp 10). One unit (¥10 000) increase in log(GDP) was associated with a 0.93 (95% CI 0.51–1.36) times increase of log(age-standardised incidence) in women and a 0.90 (0.50–1.31) times increase of log (age-standardised incidence) in men. The corresponding Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.52 (p=0.0017) in women and 0.60 (p=0.0002) in men. The regression coefficient of log(age-standardised incidence) on log-transformed number of hospital beds per 1000 people was 0.83 (95% CI 0.38–1.28) in women and 0.83 (0·42–1·24) in men; and the corresponding Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.44 (p=0.010) in women and 0.52 (p=0·0019) in men. Similar findings were observed when we only included the papillary thyroid cancer cases (appendix p 11).

Despite limitations due to possible ecological fallacy, we found that overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer occurs more often in regions where people have increased accessibility and affordability of health care than in other areas. No organised screening programmes for thyroid cancer exist in China, but the unregulated nature of the offer of medical services might lead to a large number of unnecessary check-ups. Thyroid ultrasound is included in the checklist of services in many health examination centres in China, especially under the scheme of urban employee-based basic medical insurance. The predominant fee-for- service payment method might have worsened the situation by creating incentives for hospitals to encourage more examinations. A national survey showed that the prevalence of thyroid nodules detected by ultrasonography was 20·4% in adults from the general populations.The large reservoir of subclinical disease in the general population, combined with the increasing use of non-evidence-based and extensive examinations, might have driven the high proportion of overdiagnosis in the urban areas.

Although rural areas were less affected by overdiagnosis than their urban counterparts, overdiagnosis cannot be ignored in these areas for at least two reasons. First, uneven development was seen within rural areas. For example, Jiashan county, where we observed substantial overdiagnosis, is among the top 100 counties in China in terms of comprehensive strength and development. Second, the rate of urbanisation has been accelerating in China over the past four decades. With the fast socioeconomic transition, the trends of thyroid cancer overdiagnosis observed in urban areas could potentially spread to rural areas if no regulation measures are available.

In conclusion, we found that many registries in China, predominantly in urban areas, seem to display the typical epidemiological features of overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer. These features include a large geographical variability in the incidence of the disease; a fast increase in incidence over a short period of time without a corresponding increase in mortality; a large proportion of papillary carcinomas; a great distortion of age-specific curves; and a positive correlation with indicators that are proxies of availability and access to health care, such as GDP per capita and number of hospital beds, suggesting that overdiagnosis has a major role in the regional variation of incidence of thyroid cancer.

Overall, our analyses indicate a possible sizeable problem of over- diagnosis of thyroid cancer in several urban cities in China. Individuals who are overdiagnosed with thyroid cancer undergo heavy and unnecessary treatments (including surgical removal of the thyroid gland and lifelong hormonal replacement therapy), which implies substantial impairment of patients’ quality of life and also relevant economic costs for patients and the health system. Thyroid cancer overdiagnosis is an example of medical service overuse, which is a major challenge to increase health service equality and reduce the governmental expenditure simultaneously. Our findings from China—a country rapidly transitioning to a higher level of socioeconomic status—should be an early warning to this emerging economy and other countries at a similar stage of development.